News content has a powerful impact on society and politics. Nowadays, a vast amount of information is available through the internet, which could reduce its transparency and increase the opportunity for news slant. People consume a lot of different kinds of media and rely on them as news source while often simply assuming that it is reliable. Slant is defined as the more or less favourable news coverage of an individual or group, which can be due to reality and bias. Slant can be explicit if people are aware of it, but implicit or unconscious if it is something they don’t realize. People have to recognize slants to tackle them fully. News slants can affect the selection of events and stories published, the perspective from which they are written, and can affect newspaper readers. We hypothesize that these slants manifest not only in what news describes but where they place emphasis, how they frame events, and what they keep silent about.

News

https://www.mdpi.com/2078-2489/16/4/330

On 2 April 2025, Orsolya Ring delivered a lecture at the Central European University (CEU) as part of the Borderless Knowledge: What Can AI Offer to Science? (“Határtalan tudás: Mit adhat az AI a tudománynak?”) event. In her presentation, she explored how artificial intelligence (AI) is transforming academic research, with a particular focus on its role in big data-driven studies — especially in processing the textual data widely used in the Social Sciences. Drawing on illustrative examples, she demonstrated how large language models can support the automated analysis of news media and help identify underlying patterns within it. She underscored that AI not only enhances the efficiency of scholarly work but also introduces new perspectives to empirical research.

Further details of the event can be found here.

https://intersections.tk.hu/index.php/intersections/article/view/1296

Our project was one of the organizers of the Budapest Methods Workshop, held with great success in Budapest. The event brought together over 50 international participants, including many young scholars.

Several members of our project team delivered presentations:

- Jakub Stauber: The Narratives of the War in Ukraine in Czech News Media

- Krzysztof Rybinski: Leveraging Large Language Models for Comprehensive Psychological Analysis: Insights from Four Theoretical Frameworks

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s42001-024-00325-z

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10579-023-09717-5

Events

On 2 April 2025, Orsolya Ring delivered a lecture at the Central European University (CEU) as part of the Borderless Knowledge: What Can AI Offer to Science? (“Határtalan tudás: Mit adhat az AI a tudománynak?”) event. In her presentation, she explored how artificial intelligence (AI) is transforming academic research, with a particular focus on its role in big data-driven studies — especially in processing the textual data widely used in the Social Sciences. Drawing on illustrative examples, she demonstrated how large language models can support the automated analysis of news media and help identify underlying patterns within it. She underscored that AI not only enhances the efficiency of scholarly work but also introduces new perspectives to empirical research.

Further details of the event can be found here.

On October 17, 2024, Jakub Stauber, guest speaker gave a lecture at the HUN-REN Centre for Social Sciences Institute for Political Science titled The Narratives of the War in Ukraine in Czech News Media.

Jakub Stauber is an assistant professor at the Institute of Political Science of Charles University in Prague. The guest lecture focused on applying supervised machine-learning methods to detect the presence of Russian and Western narratives about the war in Ukraine. Based on a unique corpus of Czech main news media outlets, the presented analysis demonstrated the capabilities and possible limitations of the newly fine-tuned deBERTa model.

https://www.comptextconference.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/Comptext-2024-program.pdf

https://www.comptextconference.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/Comptext-2024-program.pdf

Posts

The press is commonly referred to as the fourth estate. The term can be traced back to the traditional division of state power into three separate branches. This designation refers to the significant role that the media plays in the functioning of modern states. At first glance, it may seem peculiar to equate it with the executive, legislative, and judicial powers, but it is worth considering that except for the least developed countries, most citizens everywhere obtain their information about politics and state affairs from the press in one way or another. Considering this, it is easy to see the crucial role that the media plays in the functioning of the state, as it determines when, how, and what information people can receive. Consequently, accurate and fact-based reporting is in everyone’s interest. More…

Mi a média elfogultság?

A sajtóra szokás úgy utalni, mint a negyedik hatalmi ág, a kifejezés a állami hatalom tradicionális hármas megosztására vezethető vissza. Ez a megjelölés a média modern államok működésében betöltött meghatározó szerepére utal. Elsőre talán különösnek tűnhet a végrehajtó, törvényhozó és bírói hatalommal egy szintre emelni, viszont érdemes figyelembe venni, hogy ma már a legelmaradottabb országok kivételével mindenhol az állampolgárok döntő többsége a politikával és állam ügyekkel kapcsolatos információit valamilyen módon a sajtóból szerzi. Ennek fényében könnyű belátni, hogy milyen meghatározó szerepe van az állam működésében a médiának, hiszen az itt jelenlévő döntéshozókon múlik, hogy miről, mikor és hogyan hallunk. Ebből kifolyólag pedig a pontos és tényszerű híradás mindannyiunk érdeke.

Az egyes médiumok a befolyásos pozíciójukból eredően megtehetik, hogy bizonyos aktoroknak, legyenek azok például pártok, politikusok, gazdasági szervezetek, mozgalmak vagy lobbi csoportok kedvezzenek a híradásukkal. Amikor egy médium ilyen módon favorizál egy vagy több aktort, akkor média elfogultságról beszélünk. A szakirodalomban számos definíció van a média elfogultságra vonatkozóan, de ezek mind kisebb nagyobb eltérésekkel ezt a fajta részrehajlást írják le (Entman, 2007; Groeling, 2013; Stevenson és mtsai., 1973). Az egyes sajtótermékek favoritizmusának számos oka lehet. Gyakran tulajdonosok nem a profiért üzemeltetik ezeket a vállalkozásokat, hanem mert lehetőséget ad a számukra, hogy az adott ország közbeszédére hatást gyakoroljanak (Gentzkow és mtsai., 2015). Ilyenkor az maga a médium működtetésének a célja legalább részben az, hogy egy adott nézőpontot favorizáljon és népszerűsítsen.

Az egyes tulajdonosok preferenciáin kívül magyarázattal szolgálhatnak még részben a szerkesztők preferenciái, illetve az adott médiumok működtető vállalkozás gazdasági érdekei. Egy másik gyakori oka a média elfogultságnak a fogyasztók igényeinek való megfelelési kényszer. A feltételezés, miszerint az elfogulatlan hírek a leginkább hasznosak és így kelendőek is, gyakran nem teljesül be. Az olvasók a gyakorlatban szeretik viszont látni a saját véleményeiket és elfogultságaikat. Korábbi kutatások, amelyek a fogyasztók preferenciái mentén vizsgálták az elfogultságot azt mutatták ki, hogy a fogyasztói preferenciák az elfogultság terén jelenlévő eltérések egy jelentős részét megmagyarázzák (Gentzkow & Shapiro, 2010). Végezetül pedig azt is szükséges kiemelni, hogy gyakran az egyes államok is igyekeznek a médiájukra hatást gyakorolni, vagy nyomásgyakorlással vagy pedig pénzbeni ösztönzők segítségével.

A sajtó részrehajlás egyes eseteinek többféle kategorizálása is elérhető az érdeklődő olvasó számára (Groeling, 2013; Shultziner & Stukalin, 2021). Jelen esetben viszont praktikusabb áttekinteni néhány formát ezek természetesen csak ideáltípusok, tehát a gyakorlatban lévő esetek nem feltétlen felelnek meg tökéletesen nekik lehet, hogy kettőre vagy többre is hasonlítanak, ennek ellenére segítenek megfoghatóbbá tenni az eddig elhangzottakat, és megkönnyítik az elfogultság felismerését.

Információ kihagyása:

Információ kihagyásáról arról beszélünk, amikor egy híradás adott témát egyoldalúan kezel az által, hogy az egyik fél állításait vagy nézőpontját nem emeli be. Ennek következtében a hír olvasó/néző nem kapja meg a teljes információt és egy torz kép alakul ki benne.

Források szelekciója:

Az egyes híradások gyakran hivatkoznak szakértőkre és új kutatásokra, ilyenkor szakemberek munkájának eredményét osztják meg a nagyközönséggel, ami természetesen hasznos. Ugyanakkor a valóságban általánosságban igaz, hogy a fontosabb, kurrens kérdések kapcsán nem áll fel általában konszenzus szakértők között. Egy elfogult médium mégis azt a látszatot keltheti, hogy létezik egy ilyen konszenzus az által, hogy szelektíven választja ki a forrásokat, csak azokat emeli be a híradásba, amelyek egy adott nézőponttal vannak összhangban. Így pedig azt a látszatot kelthetik, hogy az-az oldal tudományosan legitimált ellentétben az ellenvéleménnyel.

Történetek szelekciója:

A történetek szelekciója talán a legfontosabb formája az elfogultságnak, abból kifolyólag, hogy bizonyos értelemben elkerülhetetlen. Minden médium több potenciális hír anyaggal rendelkezik, mint amennyi a végleges híradásba jut. Tehát szükségszerű valamilyen szelekciót, amelyre a szerkesztő elfogultsága is hatással van, még akkor is, hogyha nem áll szándékában torz képet adni az olvasóknak. Természetesen, ha valakinek az explicit célja, bizonyos szempont szerint történeteket kiválasztani, akkor a végtermékre gyakorolt hatás jóval jelentősebb.

Elhelyezés:

Az újságoknál a címlapon szereplő hírek jóval emlékezetesebbek és az emberek nagyobb százaléka is olvassa el őket, ehhez hasonlóan bizonyos időpontokban nagyobb a hírek nézettsége stb. tehát általában elmondható, hogy a sajtótermékeknek van lehetősége bizonyos híreket kiemelni, illetve másokat a háttérbe helyezni. Ez alapján pedig belátható, hogy egy elfogult szerkesztő felhasználhatja ezt, hogy a saját preferenciái szerint árnyalja a fogyasztók által kapott híreket.

Az eddigiekben részleteztük, hogy az egyes médiumok sokféle módon és sok különböző okból kifolyólag lehetnek elfogultak. Mindezekből természetesen nem következik, hogy nem érdemes tájékozódni és a hírekete követni. Fontos szem előtt tartani, hogy a média nem egyetlen egységes aktor, hanem egy kategória, amelyen belül megszámlálhatatlan szereplő van jelen. Ezeket a szereplőket megint csak különböző érdekek különböző irányba húznak, nem is beszélve, azokról, akik számára fontos az újságírói etika. Ebből a sokféleségből kifolyólag a legbiztosabb védelem az elfogult híradásokkal szemben, hogyha több forrásból is tájékozódunk. Továbbá azt is sokat segít, hogyha szkeptikusak vagyunk a heves érzelmi töltettel rendelkező hírekkel, vagy a konfliktusok fekete-fehér ábrázolásával szemben.

Hivatkozott tanulmányok

Entman, R. M. (2007). Framing Bias: Media in the Distribution of Power. Journal of Communication, 57(1), 163–173. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2006.00336.x

Gentzkow, M., & Shapiro, J. M. (2010). What Drives Media Slant? Evidence From U.S. Daily Newspapers. Econometrica, 78(1), 35–71. https://doi.org/10.3982/ECTA7195

Gentzkow, M., Shapiro, J. M., & Stone, D. F. (2015). Chapter 14 – Media Bias in the Marketplace: Theory. In S. P. Anderson, J. Waldfogel, & D. Strömberg (Szerk.), Handbook of Media Economics (Köt. 1, o. 623–645). North-Holland. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-444-63685-0.00014-0

Groeling, T. (2013). Media Bias by the Numbers: Challenges and Opportunities in the Empirical Study of Partisan News. Annual Review of Political Science, 16(1), 129–151. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-040811-115123

Shultziner, D., & Stukalin, Y. (2021). Distorting the News? The Mechanisms of Partisan Media Bias and Its Effects on News Production. Political Behavior, 43(1), 201–222. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-019-09551-y

Stevenson, R. L., Eisinger, R. A., Feinberg, B. M., & Kotok, A. B. (1973). Untwisting The News Twisters: A Replication of Efron’s Study. Journalism Quarterly, 50(2), 211–219. https://doi.org/10.1177/107769907305000201

Measuring media bias has long been an unresolved problem in quantitative research. Given the highly politically nuanced nature of the problem, it is worth briefly reviewing the main research directions, problems, and possible solutions to the issue of how bias can be measured. What do we call bias? How can we determine whether a given medium is biased or objective? These are difficult questions since determining bias is inherently subjective, but in this post, we will try to go around the topic and give you some ideas.

In our highly mediated world, it is more important than ever before to get an accurate picture of the reliability of our news sources, not only for us but also for researchers in the field. Measuring media bias is a decisive area of research in many respects. It helps us understand the fault lines present in our societies, the impact of economic interests on information flow, and the state of our democracies. However, measuring bias is far from trivial. In the following, we will review the challenges researchers face on the subject and the methods they use to measure media bias. This not only gives us insight into the activities of researchers but also helps us better understand the characteristics of bias within the media.

If we want to assess the bias of individual media outlets in any way, we must face two significant challenges, which can be called subjectivity and the unobservable population (Groeling, 2013). The problem of subjectivity is relatively simple. It refers to the fact that different news consumers will have different opinions about whether a particular article or report is biased, or even which direction it is biased in. One reason for this is that individuals themselves have preferences and preconceptions. They have ideological and political preferences, which may make them more inclined to view news as biased against their own positions. This is particularly common in cases where politicians refer to a hostile media environment; it is common for both sides of a debate to simultaneously claim that the press is biased and hostile towards them.

Additionally, news consumers also have preconceptions about individual outlets. Whether a piece of news is biased and in what sense it is biased can be judged differently depending on the source, as individuals already have some idea before consuming the news about whether the source is biased. To avoid this problem, researchers use tools that do not require subjective, individual judgment.

The second significant problem is the unobservable population. First, here is a little context: in statistics, we distinguish between the population and the sample when conducting a survey. The population is the group from which we want to learn something. From it, we should take a sample. For instance, if our population is the voting-age citizens of a country, then our sample would be the people we contacted and surveyed during our research. Media outlets operate similarly. Their population is all the news they receive, much larger than the information they report. This is a problem for researchers because they only encounter the sample, i.e., the information that made it into the news; they can never see the whole population. Consequently, they cannot know whether a particular media outlet was biased in any way in selecting the news. Often, when accused of bias, media outlets refer to only providing unbiased information about relevant news and cannot control whether these are favorable or unfavorable to anyone. Without the invisible population, the only reference point available to researchers is the reporting of other media outlets. Therefore, studies often do not attempt to explore bias in absolute terms but only comparatively examine it by comparing two or more different news sources.

When defining media bias, we discussed how bias can appear in diverse ways. Similarly, the methods of measuring it are also eclectic, as we will see. Most studies deal with print media because it has been the dominant news source in the past, and it is relatively easier to obtain the necessary data for analysis than television or radio broadcasts. Another characteristic of these studies is that they primarily focus on the United States, but to a lesser extent, Western Europe is also overrepresented.

We have detailed the difficulties researchers face so far; to nuance this, let’s start with the simplest method possible. In the USA, it was common for some media outlets to explicitly declare which party they supported, but this is no longer typical today; only analyses of the past rely on such explicit endorsements (D. Ho & Quinn, 2008). A modern equivalent is when the editorial staff of individual media outlets takes a stand on specific issues (Ansolabehere, 2006; D. E. Ho & Quinn, 2007; Puglisi & Snyder, 2015). This method based on “self-declaration” not only involves less work but is as objective as measuring bias can be, and it does not require the relative comparison of outlets. It allows us to assess how much of the press segment takes a stand in one way or another. The disadvantages are that we do not get information about the extent of bias, and only statements related to parties or politicians can be examined this way.

Another approach examines the sources cited by the media outlet, such as opinion pollsters, who also have biases. If we consider this bias known, then we can infer the bias of individual news sources based on how often they refer to different opinion pollsters; if they refer more often to those with certain biases, then they are likely biased (Groeling, 2008). In this example, we talked about opinion pollsters, but research of this nature has also been conducted with think tanks and other opinion leaders (Gans & Leigh, 2012; Groseclose & Milyo, 2005). It has also been examined what kind of images are displayed of certain politicians, although a challenge here is to judge which images are favorable and which are unfavorable (Hehman et al., 2012). In television broadcasts, an important question is how often certain politicians appear, and it is a significant advantage if a politician can convey their position directly to viewers in their own words.

Finally, the most innovative studies use a method called text mining. The essence of this approach is to convert texts into numerical data (using complex procedures not worth detailing here) for subsequent measurement. With these procedures, we can examine, for example, the sentiment of texts, whether they are positive or negative (Niven, 2003; Schiffer, 2006). While this approach has the allure of novelty, it still does not provide a perfect solution. Take sentiment analysis, for example; if a party typically appears in negative-toned articles, it does not necessarily mean that the negative tone refers to the party itself. Of course, with a sufficiently large sample, the correlation exists, but it is not perfect, so the result obtained also contains some uncertainty. There are more sophisticated methods than this, and sentiment analysis itself can be executed in a thousand different ways (which greatly affects the accuracy of the measurement), but there is no perfect text-mining procedure.

From the number of approaches mentioned, it can be seen that media bias takes many forms, just as researchers are forced to employ various measurement methods, but none of them can be perfect. There is no objective methodology that provides an accurate and objective measurement of bias for articles, news reports, or media outlets. These investigations can provide snapshots and point out correlations, causes, and potential effects of bias. The reason for this limitation is primarily that the subject of the investigation is constantly changing and evolving, and to select the appropriate approach, the researcher must have a thorough understanding of the social and political context of the media being studied.

Mérhető a média elfogultsága?

A modern mediatizált világban kifejezetten fontos, hogy egy pontos képet kapjunk a hírforrásaink megbízhatóságáról, nem csak a mi, hanem a téma kutatóinak számára is. A média elfogultság mérése sok tekintetben egy meghatározó kutatási terület. Segít számunkra megérteni a társadalmainkban jelenlevő törésvonalakat, a gazdasági érdekek információ áramlásra gyakorolt hatását, és a demokráciáink állapotát. Az elfogultság felmérése viszont közel sem olyan egyszerű, mint ahogyan az első pillantásra tűnhet. A következőkben áttekintjük azokat a kihívásokat, amelyekkel a téma kutatói néznek szembe és az egyes eljárásaikat is, amelyekkel az elfogultságot szeretnék mérni. Ez nem csak a kutatók tevékenységébe nyújt betekintést, hanem abban is segít, hogy mélyebben megértsük a médián belüli részrehajlás tulajdonságait.

Ha szeretnénk valamilyen módon felmérni az egyes média orgánumok elfogultságát, akkor két meghatározó kihívással kell, hogy szembenézzünk, amelyeket nevezhetünk szubjektivitásnak és megfigyelhetetlen populációnak (Groeling, 2013). A szubjektivitás problémája kifejezetten egyszerű. Annyit értünk alatta, hogy a különböző hírfogyasztók eltérő véleménnyel fognak rendelkezni arról, hogy egy adott cikk vagy híradás elfogult-e, vagy akár arról, hogy milyen irányba elfogult. Ennek az oka egyrészt, hogy maguk az egyének is rendelkeznek preferenciákkal és prekoncepciókkal. Rendelkeznek ideológiai és politikai preferenciákkal, ezekből kifolyólag pedig hajlamosabbak lehetnek arra, hogy híreket a saját pozícióikkal szemben elfogultnak tekintsenek. Ez különösen jellemző, azokban az esetekben, ahol politikusok ellenséges médiakörnyezetre hivatkoznak, nem példátlan, hogy egy vita mindkét fele párhuzamosan azt hangoztassa, hogy a sajtó elfogult és ellenséges vele szemben. Ezenfelül a hírfogyasztók az egyes orgánumokra vonatkozó prekoncepciókkal is rendelkeznek. Azt, hogy egy hír részrehajló-e, és milyen értelemben a forrástól függően máshogy ítélhetjük meg, hiszen már a hírfogyasztása előtt rendelkezünk valamilyen elképzeléssel arra vonatkozóan, hogy a forrás részrehajló-e. Ennek a problémának az elkerülése érdekében a kutatók igyekeznek olyan eszközöket használni, amelyekhez nem szükséges szubjektív, egyéni elbírálás.

A második meghatározó probléma a megfigyelhetetlen populáció. Először egy kis kontextus a probléma elnevezéséhez: statisztikában megkülönböztetjük a populációt és a mintát, amikor egy felmérést végzünk el. A populáció az a sokaság, akiről szeretnénk megtudni valamit, ezért veszünk egy mintát, például, ha a populációnk egy ország szavazókorú népessége, akkor a mintánk az emberek, akiket felkerestünk és megkérdezünk a kutatásunk során. Ehhez hasonlóan járnak el az egyes médiumok is. Az ő populációjuk az összes hozzájuk befutó hír, ami sokkal számosabb, mint azok az információk, amelyekről ténylegesen hírt is adnak. Ez a kutatók problémája, ők csak a mintával találkoznak, vagyis azokkal az információkkal, amelyek bejutottak a híradásba, a populációt viszont sosem láthatják. Ebből pedig következik, hogy nem is tudhatják, hogy az adott médium a hírek kiválasztása során elfogult volt-e bármilyen tekintetben. Gyakran a médiumok, amikor részrehajlással vádolják őket arra, hivatkoznak, hogy ők csak a releváns hírekről pártatlanul tájékoztatnak és nem tehetnek arról, hogy ezek kinek kedvezőek vagy kedvezőtlenek. A láthatatlan populáció hiányában a kutatók rendelkezésére álló egyetlen viszonyítási pont a többi sajtótermék híradása. Éppen ezért nagyon gyakran a tanulmányok nem azt próbálkoznak az elfogultság abszolútértelemben vett felderítésével, hanem csak relatíve vizsgáljak azt, két hírforrás összevetésével.

A média elfogultság definiálása során beszéltünk a részrehajlás megjelenéseinek sokszínűségéről, ehhez hasonlóan a felmérésének egyes módszerei is hasonlóan eklektikusak, ahogyan azt majd látni fogjuk. A legtöbb kutatás a nyomtatott sajtóval foglalkozik, mivel ez a múltban egy meghatározó hírforrás volt, illetve relatíve könnyebb beszerezni a szükséges adatokat, mint például televízió vagy rádióadásokat, bár utóbbiak vizsgálatára is vannak példák. További jellemzője még ezeknek a kutatásoknak, hogy elsősorban az Egyesült Államok, de kisebb mértékben Nyugat-Európa is felülreprezentált, a legtöbb kutatás erről a két helyről származó médiumokkal dolgozik.

Az eddigiekben részletesen írtuk le a kutatók előtt álló nehézségeket ahhoz, hogy ezt árnyaljuk, kezdjünk a lehető legegyszerűbb módszerrel. Az USA-ban jellemző volt, hogy egyes sajtóorgánumok közvetlenül felvállalják, hogy ők melyik pártot támogatják, ma már ez egyáltalán nem jellemző, csak a múltra vonatkozó elemzések hagyatkoznak az ilyen explicit oldalfoglalásokra (D. Ho & Quinn, 2008). Egy modern megfelelője ennek, amikor az egyes sajtóorgánumok szerkesztősége specifikus választásoknál állást foglalnak (Ansolabehere, 2006; D. E. Ho & Quinn, 2007; Puglisi & Snyder, 2015). Ez az „önbevalláson” alapuló módszer nem csak kevesebb munkával jár, de annyira objektív, amennyire csak az elfogultság vizsgálata lehet, illetve nem szükségelteti az orgánumok relatív összehasonlítását. Segítségével felmérhetjük, hogy a sajtó mekkora szegmense foglal állást ilyen vagy olyan módon. A hátrányai, hogy nem kapunk információt a pártosság mértékéről, illetve csak pártokkal vagy politikusokkal kapcsolatos állásfoglalások vizsgálhatóak így.

Egy másik megközelítés az adott média orgánum által hivatkozott forrásokat vizsgálja, például közvélemény kutatókat, akik szintén rendelkeznek elfogultsággal, ha ezt az elfogultságot ismertnek tekintjük, akkor a segítségével következtethetünk az egyes hírforrások elfogultságára, az alapján, hogy milyen gyakran hivatkoznak a különböző közvélemény kutatókra, ha bizonyos elfogultsággal rendelkezőkre egyértelműen gyakrabban hivatkoznak, akkor vélhetően elfogultak (Groeling, 2008). Ebben a példában közvéleménykutatókról volt szó, de ilyen jellegű kutatást végeztek már agytrösztök és véleményvezérek segítségével is (Gans & Leigh, 2012; Groseclose & Milyo, 2005). Továbbá vizsgálták már azt is, hogy milyen képeket jelenítenek meg egyes politikusokról, bár itt egy kihívás, hogy meg kell ítélni mely képek előnyösek és melyek hátrányosak (Hehman és mtsai., 2012).. A tévéadásoknál egy fontos kérdés, hogy mely politikusok milyen gyakran jelennek meg, az egy komoly előny, hogyha egy politikus a saját szavaival képes átadni az álláspontját közvetlenül a nézők számára.

Végezetül a leginnovatívabb kutatások az úgynevezett szövegbányászat módszerét alkalmazzák. A megközelítés lényege, hogy a szövegeket (bonyolult eljárásokkal, amelyeket itt nem lenne érdemes részletezni) számszerű adatokká alakítják, hogy utána méréseket végezzenek rajtuk. Ezekkel az eljárásokkal vizsgálhatjuk például szövegek szentimentjét, tehát azt, hogy pozitívok vagy negatívok (Niven, 2003; Schiffer, 2006). Ez a megközelítés ugyan rendelkezik az újdonság vonzerejével, viszont továbbra sem biztosít egy tökéletes megoldást. Vegyük a szentiment analízis példáját, ha egy párt jellemzően negatív tónusú cikkekben jelenik meg az nem feltétlenül jelenti, hogy a negatív tónus maga a pártra vonatkozik. Természetesen kellően nagy minta esetén az összefüggés fennáll, viszont nem tökéletes, így a kapott eredmény is tartalmaz némi bizonytalanságot. Ennél persze léteznek kifinomultabb módszerek, és magát a szentiment analízist is ezerféleképpen lehet kivitelezni (ami nagyban befolyásolja a mérés pontosságát) viszont nem létezik tökéletes szövegbányászati eljárás.

Csak az említett megközelítések számából látható, ahogy a média elfogultság is sokféle formát ölt, ugyanúgy kénytelenek a kutatók is sokféle mérési módszert alkalmazni, de egyik sem lehet tökéletes. Nem létezik objektív módszertan, ami ad egy pontos számot cikkeknek, híradásoknak vagy médiumoknak. Ezek a vizsgálódások képesek pillanatképeket adni és rámutatni összefüggésekre, az elfogultság okaira és potenciális hatásaira. Ennek a korlátozottságnak az oka elsősorban, hogy a vizsgálat tárgya folyamatosan változik és alakul, a megfelelő megközelítés kiválasztásához a kutatónak alaposan kell ismernie a vizsgált médiumok társadalmi és politikai kontextusát.

Hivatkozott tanulmányok:

Ansolabehere, S. (2006). The Orientation of Newspaper Endorsements in U.S. Elections, 1940—2002. Quarterly Journal of Political Science, 1(4), 393–404. https://doi.org/10.1561/100.00000009

Gans, J. S., & Leigh, A. (2012). How Partisan is the Press? Multiple Measures of Media Slant*. Economic Record, 88(280), 127–147. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-4932.2011.00782.x

Groeling, T. (2008). Who’s the Fairest of them All? An Empirical Test for Partisan Bias on ABC, CBS, NBC, and Fox News. Presidential Studies Quarterly, 38(4), 631–657. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-5705.2008.02668.x

Groeling, T. (2013). Media Bias by the Numbers: Challenges and Opportunities in the Empirical Study of Partisan News. Annual Review of Political Science, 16(1), 129–151. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-040811-115123

Groseclose, T., & Milyo, J. (2005). A Measure of Media Bias*. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 120(4), 1191–1237. https://doi.org/10.1162/003355305775097542

Hehman, E., Graber, E. C., Hoffman, L. H., & Gaertner, S. L. (2012). Warmth and competence: A content analysis of photographs depicting American presidents. Psychology of Popular Media Culture, 1(1), 46–52. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0026513

Ho, D. E., & Quinn, K. M. (2007). Assessing Political Positions of Media (SSRN Scholarly Paper 997428). https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.997428

Ho, D., & Quinn, K. (2008). Measuring Explicit Political Positions of Media. Quarterly Journal of Political Science, 3. https://doi.org/10.1561/100.00008048

Niven, D. (2003). Objective Evidence on Media Bias: Newspaper Coverage of Congressional Party Switchers. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 80(2), 311–326. https://doi.org/10.1177/107769900308000206

Puglisi, R., & Snyder, J. M., Jr. (2015). The Balanced US Press. Journal of the European Economic Association, 13(2), 240–264. https://doi.org/10.1111/jeea.12101

Schiffer, A. J. (2006). Assessing Partisan Bias in Political News: The Case(s) of Local Senate Election Coverage. Political Communication, 23(1), 23–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584600500476981

In earlier blog posts, we detailed how, in today’s mediatised societies, the media not only informs but also often shapes public opinion and, as such, is a crucial platform for every political actor. Since we get information about governmental activities through the media, influencing the media can be an attractive opportunity for any government. In this context, the concept of media capture arises, which is one particularly problematic manifestation of media bias. As the term suggests, media capture refers to external influence on the media; it occurs when a particular government influences media outlets, thereby manipulating the content and nature of their reporting. Such a practice raises numerous ethical and democratic concerns as it threatens media independence and pluralism, which are fundamental to democratic societies.

Media capture occurs when a particular media outlet or outlets shape their reporting based on government incentives or pressure. However, for capture to occur, the government must have tools to influence individual media outlets rather than just the entire media market. Moving forward, we will go through various manifestations and types of media bias, categorised based on the means of exerting influence. When examining media capture in scholarly literature, it is always a prerequisite to demonstrate that a particular media outlet genuinely distorts its reporting due to government intervention.

One of the most effective tools available to any government is the budget. The most practical way to selectively allocate state resources is by directing advertising spending only to certain “privileged” media outlets. In a Hungarian analysis, Ádám Szeidl and Ferenc Szűcs examined the correlation between state advertising and the content of media coverage (Szeidl & Szucs, 2021). Their analysis concluded that state advertisements significantly influence news coverage; media outlets receiving them were less likely to report on scandals examined during the research. In a previous analysis, Attila Bátorfy and Ágnes Urbán detailed how successive Hungarian governments used state advertising to shape the media environment (Bátorfy & Urbán, 2020). State advertisements influence media outlets in two ways. Firstly, they provide a financial incentive to modify their reporting. Secondly, they make it more profitable in the long term for entities aligned with the ruling party or parties to operate media outlets, thus exerting a longer-term distorting effect.

The case of public media deserves special attention. On the one hand, through positive examples, we can see that it can provide impartial and high-quality news coverage. However, all too often, public media functions as a propaganda tool for the government. This is particularly problematic considering that in most countries, the largest press organisations are some form of public media (Djankov et al., 2003). The case of Poland is illustrative in terms of public media and media capture. While the Law and Justice Party (PiS) was in power, criticism was regularly directed at the public media’s coverage (Kerpel, 2017). Subsequently, after a multi-party coalition led by the Civic Coalition (KO) came to power, significant changes in the leadership of state media led to prolonged conflicts (Politico, 2023). The situation with Hungarian public media is similar; in 2020, a leaked recording revealed that Balázs Bende explicitly instructed several public media employees that it was their job to strengthen and represent the government’s position before the European Parliament elections in March.

“Bende Balázs: The situation is as follows: everyone is aware that at the end of May, there are European parliamentary elections, and I am sure that no one will be surprised if I say that in this institution… we do not support the opposition coalition. If this statement surprises anyone, they can leave now. For those not surprised, it is not surprising that if the institution supports it, we all work accordingly. There’s no question. There will be no question about what material I want in the future. There will be no question about how to write that material. Those who don’t know can also go home and need not return.”

Bribery, as a tool, initially appears significantly similar to state advertising; a government expects certain types of coverage in exchange for financial compensation. However, two crucial differences distinguish the two cases. Firstly, bribery is not legal, unlike advertising. Secondly, the first point leads to the second: state advertising is documented, allowing citizens at least the opportunity to understand how the government influences the media, thus making the government more accountable to unoccupied press organs and civil organisations.

In countries where judicial institutions have partially or entirely fallen under government control, courts often turn against journalists and media outlets to hinder their operations. Finally, it is important to mention the most radical tool of media capture: violence against journalists, which is also frequently used for intimidation purposes and to exert control over individual media outlets.

Thus far, we have examined what media capture is and provided examples of its various manifestations and types. It is important to bear in mind that the concept of media capture is an ideal type; it generally cannot be fully matched with real cases. Governments cannot exert absolute control, and there are no governments that do not influence their countries’ media environment. Reality typically lies somewhere between the two extremes. As seen in the tools of media capture listed, examples escalate in terms of their consequences and violations of democratic norms. Generally, it can be said that the worse a country’s democratic institutions’ checks and balances function, the greater the impact the government has on the media.

Péter Gelányi

Média foglalás

A korábbi blogposztokban részleteztük, hogy az információáramlás korszakában a média nem csupán tájékoztat, hanem gyakran formálja is a közvéleményt, és mint ilyen, kulcsfontosságú platform minden politikai aktor számára. Mivel a médián keresztül értesülünk a kormányzati aktivitásról, ezért a média befolyásolása vonzó lehetőség a mindenkori kormányzatok számára. Ebben az összefüggésben felmerül a média foglalás koncepciója, mely a média elfogultság egyik különösen problematikus megnyilvánulása. Ahogyan arra már a kifejezés is utal a média külső befolyásolásáról van szó, akkor beszélünk média foglalásról, ha egy adott kormány gyakorol hatást médiumokra, ezáltal manipulálva a híradásuk tartalmát és jellegét. Egy ilyen gyakorlat számos etikai és demokratikus aggályt vet fel, mivel fenyegeti a média függetlenségét és a pluralizmust, ami alapvető fontosságú a demokratikus társadalmak számára.

Média foglalásról csak akkor beszélünk, hogyha az adott médium vagy médiumok kormányzati ösztönzők vagy nyomásgyakorlás hatására alakítják a híradásukat politikai szempontok szerint. Ehhez viszont szükséges, hogy az adott kormány rendelkezésére álljanak eszközök, amelyek segítségével hatást tud gyakorolni külön-külön az egyes médiumokra, és nem csak a média piac egészére. A továbbiakban a média elfogultság egyes megnyilvánulásain, típusain fogunk végig menni, amelyeket a szerint kategorizálunk, hogy mi a hatásgyakorlás eszköze. A média foglalás szakirodalomban történő vizsgálata során mindig feltétel annak a kimutatása, hogy az adott médium valóban kormányzati tevékenység hatására torzítja a híradását.

A mindenkori kormányzat rendelkezésére álló egyik leghatékonyabb eszköz a költségvetés. A legpraktikusabb módja, hogy az egyes állami erőforrásokat szelektívan, csak bizonyos „jutalmazott” médiumoknak juttassák el a reklámok vásárlása az adott médiumokban. Egy magyarországi elemzés során Szeidl Ádám és Szűcs Ferenc az állami reklámok összefüggését vizsgálták az adott médiumok híradásának tartalmával (Szeidl & Szucs, 2021). Az ellemzésük konklúziója szerint az állami reklámok szignifikáns hatással vannak a híradásra, azok a médiumok, amelyek részesültek bennük jelentősen kisebb valószínűséggel számoltak be a kutatás során vizsgált botrányokról. Egy korábbi elemzésben Bátorfy Attila és Urbán Ágnes rsézletezték, hogy milyen módon használták az egymás követő magyar kormányok a média környezet alakítására az állami reklámokat (Bátorfy & Urbán, 2020). Az állami reklámok kétféle képpen is hatástgyakorolnak a médiumokra. Az első és egyértelműbb eset, hogy egy pénzbeni ösztönzőt adnak, amivel megpróbálják rávenni őket, hogy módosítsák a híradásukat. A mmásodik pedig, hogy hosszú távon jövedelmezőbbé teszik, hogy olyan szereplők működtessenek médiumokat, akiknek a prioritása összhangban van a kormányzó párttal vagy pártokkal, így egy hosszabb távú torzító hatást is gyakorol.

A közmédia esete különös figyelmet érdemel. Egyrészt pozitív példákon keresztül láthatjuk, hogy képes pártatlan és magas minőségű híradást biztosítani, ugyanakkor túlságosan is gyakran a közmédia a kormány propaganda orgánumaként funkcionál. Ami még inkább problematikus, annak fényében, hogy a legtöbb országban a legnagyobb sajtóorgánum valamilyen fajta közmédia (Djankov és mtsai., 2003). Lengyelország esete szemléletes a közmédia és a média foglalás szempontjából, ameddig a jog és igazságosság pártja (PiS) volt hatalmon rendszeresen kritikák érték a közmédia híradását (Kerpel, 2017) miután pedig egy több párti koalíció, élén a polgári koalícióval (KO) a jelentős változások az állami média vezetőségében hosszabb távú konfliktusokat idézet előtt (Politico, 2023). A lengyelhez hasonló a magyar közmédia helyzete, 2020-ban kiszivárgott egy hangfelvétel, amelyen Bende Balázs közvetlen módon egyértelművé tette a közmédia több munkatársának számára, hogy munkájuk része, hogy a márciusi Európai Parlament választások előtt a kormányzati álláspontot erősítsék, képviseljék szemben az ellenzékivel.

„A következő a szituáció: mindenki tisztában van vele, hogy május végén európai parlamenti választások vannak, és biztos vagyok benne, hogy senkit nem ér váratlanul, ha azt mondom, hogy ebben az intézményben…nem az ellenzéki összefogást támogatják. Ha ez a kijelentés valakit váratlanul ér, az most menjen haza. Akit ez nem ér váratlanul, azoknak az a kijelentés sem lehet váratlan, hogy az intézmény, ha támogatja, az azt jelenti, hogy ennek megfelelően dolgozunk mindannyian. Nincs kérdés. A jövőben olyan kérdés sincsen, hogy milyen anyagot szeretnék kérni. Olyan kérdés sincsen, hogy hogyan kell megírni azt az anyagot. Aki nem tudja, az is elmehet haza, és nem is kell többet jöjjön.”

(Telex, 2020)

A vesztegetés, mint eszköz első pillantásra jelentős mértékben hasonlít az állami reklámok esetére, adott kormány bizonyos fajta híradást vár el egy pénzbeni ellenszolgáltatásért cserébe. Ugyanakkor két fontos pontban eltér egymástól a két eset. Az első egyzserűen az, hogy a vesztegetés a reklámozással szemben nem legális. A második pedig az elsőből következik ugyanis az állami reklámok dokumentáltak és ebből következően az állampolgároknak van legalább lehetősége arra, hogy átlássák, hogyan és milyen hatást gyakorol az állam a médiára, így a kormány is elszámoltathatóbb el nem foglalt sajtó orgánumok és civil szervezetek által.

Azokban az országokban pedig, ahol az igazságszolgáltatás intézményei részben vagy egészben kormányzati kontroll alá kerültek a bíróságokat gyakran az újságírók és sajtóorgánumok ellen fordítják, hogy ezek működését ellehetetlenítsék az ő működésüket. Végezetül pedig fontos megemlíteni a média foglalás legradikálisabb eszközét, az újságírók elleni erőszakot, amely szintén gyakran kerül felhasználásra a megfélemlítés céljából illetve, hogy ezáltal kontrolt gyakoroljanak az egyes médiumok felett.

Az eddigiekben végig vettük, hogy mi is a média foglalás, illetve példákat hoztunk fel annak néhány megnyilvánulására, típusára. Fontos észben tartani, hogy a média foglalás fogalma egy ideál típus, vagyis általában nem feleltethetőek meg neki valós esetek. A kormányok nem tudnak abszolút kontrolt gyakorolni, illetve nem léteznek olyan kormányok sem, amelyek egyáltalán nem befolyásolják az országuk média környezetét. A valóság általában majdnem mindig a két extrém között helyezkedik el. A média foglalás felsorolt eszközein is láthattuk, hogy a példák egyre eszkalálódnak a következményeik szempontjából és a demokratikus normák megsértésének szempontjából is. Általában elmondható, hogy minél rosszabbul működnek egy adott ország demokratikus intézményei, a fékek és ellensúlyok, annál nagyobb hatást gyakorol az adott ország kormány a médiára.

Hivatkozott tanulmányok:

Bátorfy, A., & Urbán, Á. (2020). State advertising as an instrument of transformation of the media market in Hungary. East European Politics, 36(1), 44–65. https://doi.org/10.1080/21599165.2019.1662398

Djankov, S., McLiesh, C., Nenova, T., & Shleifer, A. (2003). Who Owns the Media? The Journal of Law and Economics, 46(2), 341–382. https://doi.org/10.1086/377116

Kerpel, A. (2017). Pole and Hungarian cousins be? A comparison of State media capture, ideological narratives and political truth monopolization in Hungary and Poland. SLOVO Journal, 29(1), 68–93.

Kiszivárgott hangfelvételen magyarázzák a köztévé vezető szerkesztői, hogy „az intézményben nem az ellenzéki összefogást támogatják”. (2020, november 12). telex. https://telex.hu/belfold/2020/11/12/kozmedia-kiszivargo-hangfelvetel-ellenzeki-osszefogas-bende-balazs

Poland’s media revolution turns into a political battle. (2023, december 27). POLITICO. https://www.politico.eu/article/poland-media-revolution-pis-law-and-justice-tusk-duda/

Szeidl, A., & Szucs, F. (2021). Media Capture Through Favor Exchange. Econometrica, 89(1), 281–310. https://doi.org/10.3982/ECTA15641

In this blog post, we will review a text-mining mini-research examining media bias, giving us insight into the steps of analysis and the decisions made by researchers, which significantly influence the results obtained. The vast majority of people encounter scientific results only through the media. Typically, they only have the opportunity to familiarise themselves with a summary of the research conclusion (often presented misleadingly). In contrast, the process leading to that conclusion remains a black box. Consequently, we may have too much or too little trust in these results.

We might have too little trust because we cannot see the research process and find it difficult to trust it. Alternatively, we might be overly confident in a particular result because, lacking knowledge of the research process, we are unaware of its limitations and the research decisions that influenced the obtained result. In reality, individual studies almost always contribute to a deeper and more comprehensive understanding of their topic, but their conclusions are not absolute; they are the result of the work of many researchers over the years. In other words, science is an iterative process. This is particularly true for social sciences, where the approach to the topic under investigation is crucial.

The subject of our mini-research is the change of ownership of two Hungarian online media products, Origo and Index, and the perceived changes in their reporting. Origo and Index have many similarities in several aspects. Origo’s news portal was sold in February 2016, with the new owners indirectly linked to the Hungarian government (24.hu, 2016). Following the change in ownership, numerous employees were laid off, and significant changes occurred in Origo’s reporting. A similar case occurred with Index in 2020 (24.hu, 2020), followed by protests (hvg.hu, 2020). Generally, the change in ownership of these two mentioned newspapers is perceived in public discourse as affecting their reporting. To investigate this question, we collected data from online Hungarian media sources. In addition to articles surrounding Origo and Index ownership changes, we collected articles from seven other online media outlets for comparison: 168.hu, 24.hu, hvg.hu, magyarnarancs.hu, telex.hu, hiradó.hu, and finally magyarnemzet.hu.

Every research study has a hypothesis, which is a preliminary assumption regarding the results of the experiment or analysis. In this case, we hypothesise that after the change of ownership, the articles of Origo and Index will be more in line with the communication of the Hungarian government than before and less in line with the communication of the opposition in Hungary. After formulating our hypothesis, the next step is operationalisation. During operationalisation, we must turn our preliminary abstract ideas into measurable, concrete phenomena. In practice, we must define an exact method for determining whether a media report aligns with government or opposition communication.

In this case, we use text mining tools (which is already a significant research decision). Among these, a relatively simple approach is examining word frequencies. Suppose we have a list of words that we believe are associated with government or opposition communication. In that case, we can look at the frequency of these words in the articles we have collected. The approach of this mini-research bears significant resemblance to the analysis of Matthew Gentzkow and Jesse M. Shapiro, but with some simplifications (Gentzkow & Shapiro, 2010). First, we need to determine the list of words that we believe are associated with government and opposition communication. We can use parliamentary speeches to select two-word lists through relative frequency analysis. Thus, we select words that government representatives use more frequently than opposition representatives and vice versa. Speeches by independent representatives and the house speaker are excluded from the data in advance. This step involves two important research decisions: firstly, we used parliamentary speeches instead of other sources, such as politicians’ Facebook posts, party programs, or news content appearing on the parties’ official websites, all of which could have been potential alternatives. The second important decision we made was to collect two-word lists instead of creating a separate list for each party present in parliament.

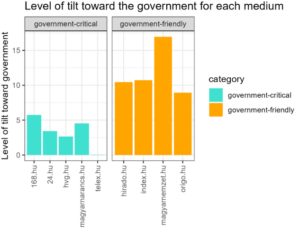

Following this, we can compare our list of words with the vocabulary of the collected media to see the relationship between the two. This relationship is visible in the first figure.

It is important to emphasise that these articles were created following the change of ownership, which is why Index and Origo were categorised based on expert assessment as close to the government. The chart’s columns show the difference in occurrences between expressions associated with the governing party and those associated with the opposition, subtracting the latter from the former. Thus, in the case of media categorised as close to the government, the ratio of expressions related to the governing party per article is much higher, and both Index and Origo seem to be closer to these media outlets. Among them, Magyar Nemzet stands out with particularly high values. Another important observation is that even in the case of media marked as critical of the government, expressions used more frequently by representatives of the governing parties are in the majority. This is the fact that being in the governing position generally allows for more opportunities to shape public discourse. Parties in the governing position take action and pass laws, while parties in the opposition are relegated to reacting and formulating alternatives. It is significantly easier for the former to get into the news.

After comparing the occurrence of words over a given time interval, we can now examine the temporal changes in the case of Index and Origo during the period surrounding the change of ownership. This relationship is visible in the second and third figures.

There is understandably significant fluctuation in the daily occurrences of the examined words, so we smoothed out the trend lines in the above charts using moving averages. It is important to highlight two things: firstly, we can observe that in both cases, the proportion of expressions associated with the government coalition has increased. However, based on our hypothesis, the relationship is not as straightforward as we might assume. There are several outliers in the data, and the period before the change of ownership cannot be considered stable at all, with the most notable observation occurring for Index in 2020. If we delve into the occurrences of words, we can see that the outliers are related to the coronavirus pandemic, reflecting the extra attention paid to government communication. This case highlights the limitations of our approach. While our results show a correlation between our word lists and the orientation of the media, and to some extent, we can detect changes in Index and Origo using this method, the orientation of the media is not the sole determinant of how much they reflect government or opposition communication.

In this example, we certainly did not see definitive results; the model would require significant fine-tuning. However, our goal was not to present definitive results but to highlight how research decisions influence the results of studies. Of course, the fact that a study could have been conducted in various ways does not mean that all results are equally valid. The validity of the present results is also called into question by the imperfections of our approach; we collected relatively little data, could have weighted the expressions according to their relevance, filtered them more effectively, could have taken into account their semantic similarities, etc. And we haven’t even mentioned the preparation of the texts, a process that could warrant a whole separate blog post. There are no perfect research methods, but better and worse ones. If we occasionally delve into the methodology of a study, it helps us understand how reliable its results are and what limitations the study’s conclusions have.

Péter Gelányi

Média elfogultság vizsgálata egy gyakorlati példán keresztül

Ebben a blogposztban egy média elfogultságot vizsgáló szövegbányászati mini-kutatást fogunk áttekinteni, ennek keretében pedig lehetőségünk lesz betekintést nyerni az elemzés lépéseibe, azokba a döntésekbe, amelyeket a kutatók hoznak és amelyek jelentős mértékben befolyásolják a kapott eredményeket. Az emberek döntő többsége csak a médián keresztül találkozik tudományos eredményekkel. Ilyenkor jellemzően csak a kutatás konklúziójáról készített rövid összefoglalóval van lehetősége megismerkedni (amelyet gyakran félrevezető módon prezentálnak) a folyamat maga, ami az adott konklúzióhoz vezet egy fekete dobozban marad. Ennek következménye, hogy párhuzamosan lehet túl sok és túl kevés bizalmunk ezekben az eredményekben.

Túl kevés bizalmunk lehet abból kifolyólag, hogy nem látunk rá a kutatási folyamatra és így nehéz bele helyezni a bizalmunkat. Illetve ehhez hasonló okból lehetünk túlságosan is magabiztosak egy adott eredményben, mivel a kutatási folyamat ismeretének hiányában nem lehetünk tisztában annak a korlátaival és azokkal a kutatási döntésekkel, amelyek kihatással voltak a kapott eredményre. A valóságban az egyes tanulmányok majdnem mind hozzájárulnak a témájuk mélyebb és átfogóbb megértéséhez, viszont a konklúziójuk nem abszolút, azok az eredméynek, amelyeket tényként kezelünk mindig sok-sok kutató többéves munkájának az eredménye. Másszóval a tudomány egy iteratív folyamat. Ez hatványozottan érvényes a társadalomtudományokra, ahol a vizsgált témánk megközelítése meghatározó.

Jelen mini-kutatásunk témája két magyar online sajtó termék az Origo és az Index tulajdonos váltása, és az ezzel járó vélt változás a híradásukban. Az Origo és az Index esete nagyon sok ponton párhuzamokkal rendelkezik. 2016 februárjában eladásra került az Origo hírportál, az új tulajdonosok pedig közvetetten a magyar kormányhoz köthető személyek voltak (24.hu, 2016). A tulajdonváltást követően számos alkalmazot felmondott, az Origo híradásában pedig jelentős mértékű változás ment végbe. Ezzel közel azonos eset zajlott le az Index esetében is még 2020-ban (24.hu, 2020). Az Index tulajdonváltását tüntetések is követték (hvg.hu, 2020). Általánosságban elmondható tehát, hogy a közbeszédben a két említett lap tulajdon cseréje úgy jelenik meg, mint amely mögötti motiváció a híradásuk. Ennek a kérdésnek a vizsgálatához gyűjtést végeztünk online magyar médiumok szövegeiből. Az Origo és az Index tulajdonváltás körüli cikkein kívül még további 7 online médium cikkeit is begyűjtöttük ahhoz, hogy legyen mivel összehasonlítani az Origo és az Index eredményeit. Ez a hét médium a: 168.hu, 24.hu, hvg.hu, magyarnarancs.hu, telex.hu, hiradó.hu és végül magyarnemzet.hu

Minden kutatás rendelkezik egy hipotézissel, ami egy előzetes feltevés arra vonatkozóan, hogy mi lesz a kísérlet, vagy az elemzés eredménye. Jelen esetben azt feltételezzük, hogy az Origo és az Index cikkei a tulajdonos váltás után nagyobb összhangban lesznek a magyar kormány kommunikációjával, mint előtte, illetve kisebb összhangban lesznek a magyarországi ellenzék kommunikációjával. A hipotézisünk megfogalmazása után a következő lépés az operacionalizálás. Az operacionalizálás során az előzetes absztrakt elképzeléseinket mérhető konkrét jelenségekké kell, hogy alakítsuk. Ez a gyakorlatban annyit tesz, hogy meg kell, hogy határozzuk egy egzakt módszert arra vonatkozóan, hogy állapítjuk meg, hogy egy médium híradása kormányzati vagy ellenzéki kommunikációval van-e összhangban.

Jelen esetben szövegbányászati eszközöket használunk (ez már önmagában egy meghatározó kutatói döntés) ezek közül egy relatíve egyszerű megközelítés a szógyakoriságok vizsgálata. Ha rendelkeznénk szavak egy listájával, amelyekről úgy véljük, hogy kormányzati vagy ellenzéki kommunikációval állnak összefüggésben, akkor megnézhetnénk ezeknek a szavaknak az előfordulási számát az általunk összegyűjtött egyes cikkekben. Jelen mini kutatás megközelítése jelentős mértékben hasonlít Matthew Gentzkow és Jesse M. Shapiro elemzéséhez néhány egyszerűsítéssel (Gentzkow & Shapiro, 2010). Ehhez persze először meg kell határoznunk azoknak a szavaknak a listáját, amelyekről úgy véljük, hogy összefüggésben állnak a kormányzati és az ellenzéki kommunikációval. Ehhez a parlamenti felszólalásokat használhatjuk fel, ezekből kiválasztunk két darab szólistát relatív frekvencia anlízis segítségével. Tehát kiválasztjuk azokat a szavakat, amelyeket kormánypárti képviselők gyakrabban használnak ellenzéki képviselőkhöz képest, és azokat is, amelyeket ellenzéki képviselők gyakrabban használnak kormánypárti képviselőkhöz képest. A független képviselők felszólalásait, illetve a házelnök felszólalásait pedig előzetesen eltávolítjuk az adatokból. Ez a lépés két fontos kutatói döntést is tartalmaz egyrészt a parlamenti beszédeket használtuk egyéb források helyett pl.: politikusok facebook posztjai, az egyes pártok programjai, vagy a pártok hivatalos weboldalán megjelenő hírtartalmak. Ezek mind potenciális alterntívák lehettek volna. A második fontos döntés amit meghoztunk pedig, hogy két szó listát gyűjtöttünk ahelyett, hogy mindegyik parlamentben jelenlévő párthoz kialakítottunk volna egy különálló listát.

A szavaink listáját ezt követően összevethetjük, az összegyűjtött médiumok szókészletével, hogy megnézzük milyen összefüggés áll fenn a kettő között. Ez a kapcsolat látható az első ábrán.

Fontos leszögezni, hogy ezek a cikkek a tulajdonváltást követő időszakban keletkeztek, ezért került mind az Index és az Origo szakértői kategorizálás alapján a kormány közeli csoportban. Az ábra oszlopain látható a kormánypárthoz köthető kifejezések és az ellenzékhez köthető kifejezések előfordulásának különbsége, előbbiből kivonva az utóbbit. Az ábrán látható tehát, hogy a kormány közeliként kategorizált médiumok esetében jóval nagyobb az egy cikkre jutó kormánypárti kifejezések aránya, mind az index és az origo is látszólag ezekhez a médiumokhoz van közelebb. Közülük a magyarnemzet kifejezetten kiugró értékkel rendelkezik. Egy másik fontos megfigyelés, hogy a kormány kritikusként megjelölt médiumok esetében is többségben vannak a kormánypártok képviselői által gyakrabban használt kifejezések ennek az oka feltételezhetően az, hogy általában a kormányzó pozíció nagyobb lehetőséget ad a közbeszéd tematizálására. A kormányzó pozícióban lévő pártok cselekednek, törvényeket hoznak, míg az ellenzékben lévő pártoknak elsősorban a reagálásra és az alternatívák megfogalmazására van lehetőségük. Előbbi számára jelentősen egyszerűbb, hogy a hírekbe jusson.

Miután összevetettük a szavak előfordulását egy adott időintervallum alatt, most megnézhetjük ennek az időbeni alakulását az Index és az Origo esetében is a tulajdonváltás körüli időszakban. Ez az összefüggés látható a második és harmadik ábrán.

A vizsgált szavak napi előfordulásában nem meglepő módon jelentős fluktuáció van, így a fenti ábrák trendvonalát mozgóátlagok segítségével simítottuk ki. Két dolgot fontos kiemelni, egyrészt valóban megfigyelhetjük, hogy mindkét esetben növekedett a komránykoalíció képviselőihez köthető kifejezések aránya, ugyanakkor az összefüggés korán sem annyira egyszerű, mint ahogy azt a hipotézisünk alapján feltételezhetnénk. Több kiugrás is van az adatokban és a tulajdonváltás előtti időszak egyáltalán nem tekinthető stabilnak, a leginkább szembetűnő az Index esetében figyelhető meg 2020-ban. Hogyha egy picit beleássuk magunkat a szóelőfordulásokba, akkor láthatjuk, hogy a kugró értékek a koronavírus járvánnyal állnak összefüggésben, amelynek tükrében nem meglepő, hogy extra figyelem irányult a kormányzat komunikációjára. Ez az eset rámutat a megközelítésünk limitációjára, az eredményeinken tényleg látszik, hogy jelen van egy összefüggés a szólistáink és a médiumok orientációja között illetve bizonyos mértékig az Index és Origo változásait is detektálhatjuk ezzel a módszerrel, viszont a médiumok orientációja nem az egyetlen meghatározója annak, hogy milyen mértékben reflektálják a kormányzati vagy ellenzéki kommunikációt.

Ebben a példában biztosan nem láthattunk definitív eredményeket, a modell jelentős finomhangolást igényelne még ahhoz, viszont a célunk nem is definitív eredmények prezentálása volt, hanem az, hogy rámutassunk, hogyan befolyásolják a kutatások eredményeit a kutatói döntések. Természetesen az, hogy egy kutatást számos különböző módon is el lehetett volna végezni nem azt jelneti, hogy mindegyik eredmény egyenlő mértékben valid. A jelen eredmények validitását is pont a megközelítésünk tökéletlenségei vonják kétségbe, viszonylag kevés adatot gyűjtöttünk, súlyozhattuk volna a kifejezéseket relevanciájuk szerint megszűrhettek volna őket jobban, figyelembe vehettük volna a szemantikai hasonlóságaikat stb. stb. és akkor még csak nem is beszéltünk a szövegek előkészítéséről, amely folyamatról egy különálló teljes blogposztot lehetne írni. Nincsenek tökéletes kutatási módszerek, de vannak jobbak és rosszabbak, hogyha alkalomadtán egy picit beleássuk magunka egy-egy kutatás módszertanába, akkor az segít nekünk belátni, hogy mennyire megbízhatóak az eredményei és milyen korlátozottságai vannak a kutatás konklúzióinak.

Hivatkozott tanulmányok:

Gentzkow, M., & Shapiro, J. M. (2010). What Drives Media Slant? Evidence From U.S. Daily Newspapers. Econometrica, 78(1), 35–71. https://doi.org/10.3982/ECTA7195

Lezárult az Origo eladása, megszólalt az új vezérigazgató. (2016, február 8). 24.hu. http://24.hu/media/2016/02/08/lezarult-az-origo-eladasa-megszolalt-az-uj-vezerigazgato/

Új Index-tulajdonos: A függetlenség kérdése szubjektív. (2020, november 24). 24.hu. https://24.hu/belfold/2020/11/24/index-fuggetlen-sajtoszabadsag-ziegler-gabor-vaszily-miklos-indamedia/

Zrt H. K. (2020, július 24). Több ezren tüntettek Orbán hivatalánál a szabad Index mellett. hvg.hu. https://hvg.hu/itthon/20200724_Elkezdodott_az_Index_melletti_tuntetes

In 2016, Ahmed Mansoor, an internationally recognised human rights activist, received an SMS from an unknown sender. The message promised information about torture committed by authorities in the United Arab Emirates, accessible through a link. Mansoor, who had previously been targeted with spyware, forwarded the message to Citizen’s Lab, an interdisciplinary laboratory specialising in phone spyware—in collaboration with Lookout Security, Citizen’s Lab determined that the link was associated with the Israeli NSO Group’s infrastructure. Clicking it would have compromised Mansoor’s device, uploading spyware onto his mobile phone (Marczak & Scott-Railton, 2016). In this blog post, we will briefly review the Pegasus scandal and then, as in the past, conduct a mini-analysis to examine the coverage of 4 Hungarian media outlets. The Pegasus case in the Hungarian press is a good example of how our news diet shapes what news we learn about, the aspects of it we’re informed about, and the significance we attribute to them.

The Israeli NSO (named after the company’s three founders, Niv, Shalev, and Omri) developed the Pegasus spyware in 2011. Pegasus can surreptitiously hack targeted phones, accessing all their communications, such as SMS, emails, calls, and other messages. Additionally, it can activate the camera or microphone on the device without the user’s knowledge, effectively turning the phone into a quasi-24/7 surveillance tool. The software is officially sold only to governments by NSO with approval from the Israeli Ministry of Defense, exclusively for monitoring targets suspected of terrorism or organised crime (Telex, 2021). Pegasus was used by Mexican authorities to capture the drug lord Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán Loera, and European authorities used it to prevent several terrorist attacks (Bergman & Mazzetti, 2022). However, the software became notorious for its misuse and abuse; it has been used all over the globe against human rights activists, collecting information on opposition politicians in Poland, which was later leaked to the Polish press (AFP, n.d. 2021), and the Saudi state also used it against women’s rights activists and journalist Jamal Khashoggi before his murder by the hands of Saudi operatives.

The software also targeted several Hungarian entities, including journalists, businessmen, media owners, the president of the Bar Association, and Attila Aszódi, a state secretary. State leaders and agencies questioned in the case did not respond whether the Hungarian government procured or used the software until November 5, 2021, when Lajos Kósa, chairman of the Defense and Law Enforcement Committee, unexpectedly claimed in an unscripted interview with RTL that the Ministry of Interior had procured the Pegasus software (Telex, 2021).

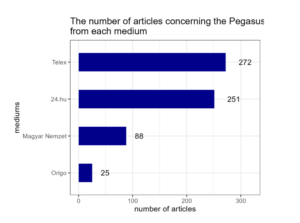

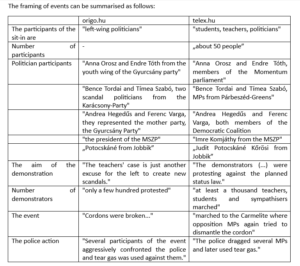

In our mini-analysis, we will examine four online media outlets: Telex and 24.hu, considered critical of the Hungarian government, and Origo and Magyar Nemzet, which are considered close to and supportive of the Hungarian government. Using the keyword “Pegasus,” we will compile a list of relevant articles from these four sources, except for Telex, where the „Pegasus” tag can be used to identify relevant articles, making our task more manageable. However, we need to manually filter out false positives for the other three media outlets. Examples include record-breaking racehorse sales, a Turkish airline, and the Pegasus constellation. Once we are sure that our collection contains only articles related to spyware, the most straightforward approach is to compare the number of articles produced by each outlet.

The results show that, as our preliminary assumptions suggested, significantly more articles were published in media outlets critical of the government regarding a scandal that was embarrassing for the Hungarian government in several aspects. Origo’s 25 articles are particularly low. In the next step, we can examine how the number of articles changes during the relevant period from July 18, 2021, to February 22, 2024 (the date of article collection).

In the second figure, we can see that in the reports of Telex and 24.hu, especially in the case of the former, a large number of articles appeared when the scandal broke, following the topic has periodically reemerged in the form of 1-2 articles per day. In contrast, the distribution of article numbers over time is much flatter for Origo and Magyar Nemzet.

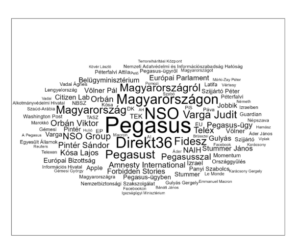

Following this, we can also look into the context in which Pegasus appears in the news of the four examined media outlets. For this, we use a slightly more complicated method called named entity recognition. With the help of a large pre-trained language model, we can identify the named entities present in our texts. A named entity is any noun that denotes something specific or unique. For example, the word “capital” is not a named entity, but “Warsaw” and “Prague” are. Furthermore, named entities include names of various institutions, organisations, personal names, email addresses, etc. From these examples, it is already apparent why named entities are useful for examining the content of articles; through the named entities of an article, we can see its most important elements in the outline. First, we separate the collected texts into those from a government-critical perspective (Telex and 24.hu) and those from a government-friendly perspective (Magyar Nemzet and Origo). Then, we gather all the named entities and count how often each occurs. Finally, we can depict the most common ones in a word cloud, where the size of each expression represents the frequency of its occurrence. The first figure shows the word cloud generated from the articles of Telex and 24.hu.

The figure shows, on the one hand, organisations related to Pegasus, such as the NSO company developing the software, and media companies that have participated in international investigative work: Direkt36, Le Monde, and Citizen Lab. Furthermore, we can see the names of politicians important in the Hungarian context of the case, such as Sándor Pintér, Lajos Kósa, Judit Varga, Péter Szijjártó, Gergely Gulyás, as well as the names of several relevant Hungarian institutions, such as the Ministry of Interior, the National Assembly, and the Information Office. Finally, we can observe echoes of the case’s international aspects. Israel appears, not surprisingly. Saudi Arabia and Morocco have also abused the software on multiple occasions, and it has been revealed that they spied on high-ranking Algerian military and political leaders using the software. Overall, the word cloud thus obtained reflects a news stream that primarily focuses on the Hungarian aspect of the case. In the fourth figure, we can view the word cloud generated from the Origo and Magyar Nemzet articles using the same method.

A technical detail regarding the fourth figure is that the words are larger; the reason for this is that they are based on fewer articles, resulting in less variance in the occurrence of individual named entities, and therefore, the sizes of the words are less differentiated. Here, the reaction to international news is less evident; some relevant Hungarian politicians’ names appear, such as Judit Varga, but the most frequently occurring names are those of Hungarian politicians who were in opposition and did not hold relevant positions of power during the surveillance of Hungarian citizens with Pegasus, such as Péter Márki-Zay, Ferenc Gyurcsány, and Gergely Karácsony. Although we also saw expressions related to the European Union in the previous word cloud, their weight is noticeably greater here. Based on this, we can infer that these two outlets placed greater emphasis on discussing reactions to the scandal in their articles.

The mini-analysis presented in the blog post is simplified in several respects, but it provides insight into the reporting on Pegasus by the four media outlets. The results show that Hungarian consumers may reach different conclusions about the significance of the Pegasus scandal depending on the sources from which they obtain their news. Additionally, they may become acquainted with different aspects of the scandal’s Hungarian dimension. The Pegasus case was chosen to illustrate this phenomenon; therefore, we may not expect similar discrepancies in politically less sensitive topics.

Péter Gelányi

Pegasus botrány a magyar média különböző lencséin keresztül

2016-ban Ahmed Mansoor, nemetközileg elismert emberjogi aktivista SMS-t kapott egy ismeretlen küldőtől. Az üzenetben információt ígérnek az Egyesült Arab Emirátusokban a hatóságok által elkövetett kínzásról, amely egy linken keresztül elérhető. Mansoor, akit a múltban már többször ért kémszoftverekkel történő megfigyelési kísérlet továbbította az üzenetet Citizen’s Lab számára, amely egy telefonos kémszoftverekre szakosodó interdiszciplináris labor. Citizen’s Lab Lookout Security-val együttműködve megállapította, hogy a link az izraeli NSO csoport infrastuktúrájához volt köthető, követése feltörte volna Mansoor eszközét, és feltöltötte volna magát a mobiltelefonra (Marczak & Scott-Railton, 2016). Ebben a blogposztban röviden áttekintjük a Pegasus botrányt, majd a korábbiakhoz hasonlóan egy mini-elemzés keretein belül megvizsgáljuk, hogy milyen mértékben tematizálta 4 magyar online médium a botrányt. A Pegasus és a magyar sajtó esete egy jó példa arra, hogy a hír diétánk, hogyan határozza meg, hogy milyen hírekről tájékozódunk, azoknak milyen aspektusairól, és ezeknek milyen jelentőséget tulajdonítunk.

Az izraeli NSO (nevét a cég három alapítója után kapta Niv, Shalev és Omri) még 2011-ben fejlesztette ki a Pegasus kémszoftvert, a Pegasus képes észrevétlenül feltörni célbavett telefonokat, eléri a rajtuk lévő összes kommuniációt, mint SMS-k, emailek, hívások és minden más üzenetet, ezenfelül a felhasználó tudta nélkül képes bekapcsolni a kamerát vagy mikrofont az eszközön ezzel egy kvázi napi 24-órás megfigyelő eszközzé alakítva át a mobilt. Az szoftvert hivatalosan csak komrányok számára árusítja az NSO az Izraeli Védelmi Minisztérium engedélyével, kizárólag terrorizmussal vagy szervezett bűnözéssel gyanusított célpontok megfigyelésére (Telex, 2021). A Pegasus segítségével fogták el Mexikói hatóságok Joaquín Guzmán Loera-t a drogbárót, másnéven El Chapo-t, európai hatóságok pedig több terrortámadás megakadályozására is alkalmazták (Bergman & Mazzetti, 2022). A szoftver viszont a vele kapcsolatos visszaélésekről híresült el, világszerte használták emberjogi aktivisták ellen, Lengyelországban ellenzéki politikusokról gyűjtöttek információkat, amelyeket késöbb a lengyel sajtónak kiszivárogtattak (AFP, é. n. 2021) illetve a Szaudi állam is felhasználta nő jogi aktivistákkal és az újságíró Jamal Kashoggi-val szemben is még a meggyilkolását megelőzően.

A szoftverrel több magyar célpontot is megfigyeltek, többek között újságírókat, üzletembereket, média tulajdonosokat, az Ügyvédi Kamara elnökét, és Aszódi Attila államtitkárt. Az ügyben kérdezett állami vezetők és szervek nem adtak választ arra vonatkozóan, hogy a magyar állam beszerezte-e vagy alakalmazta volna-e a szoftvert, egészen 2021 november 5.-ig, amikor Kósa Lajos a honvédelmi és rendészeti bizottság elnöke egy az RTL-nek adott interjúban váratlanul azt állította, hogy a Belügyminisztérium beszerezte a Pegasus szoftvert (Telex, 2021).

A mini-elemzésünkben négy db. online médiumot fogunk megvizsgálni Telex és 24.hu, amelyeket a magyar kormánnyal szemben kritikusnak tekintünk, illetve Origo és Magyar Nemzet, amelyeket a magyar kormányhoz közelállónak, azt támogatónak tekintünk. A négy orgánumból a „Pegasus” kulcsszó segítségével összegyjtjük a releváns cikkek listáját, ez alól kivétel a Telex, ahol a Pegasus, mint címke létezik megjelölve a releváns cikkeket, ami megkönnyíti a dolgunkat a másik három médiumnál viszont kénytelenek vagyunk kiszűrni a hamis találatokat manuálisan. Ezek között találunk példát rekord áron eladott versenylóra, egy török légitársaságra és a Pegasus csillagképre is. Miután biztosak lehetünk benne, hogy csak a kémszoftverre vonatkozó cikkeket tartalmazza a gyűjtésünk, akkor a legegyszerűbb megközelítés, hogy összevetjük melyik orgánumban hány db. cikk készült.

Az eredményeken látzsik, hogy az előzetes feltételezéseinknek megfelelően a kormányzattal szemben kritikus médiumokban jóval több cikk jelent meg egy olyan botrányról, amely több szempontból is kínos volt a magyar kormány számára. Az Origo 25 db. cikkje különösen alacsony. A következő lépésben megnézhetjük, hogyan alakul a cikkek száma a releváns időszak során 2021. 07. 18.-tól 2024. 02. 22.-ig (a cikkek gyűjtésének időpontja).

A második ábrán láthatjuk, hogy Telex és 24.hu híradásában, különösen az előbbi esetében nagy számban jelentek meg cikkek a botrány kitörésének elején, majd ezt követően napi 1-2 cikk keretében újra felmerült a téma néhány napos kihagyásokkal. Ezzel szemben az Origo és a Magyar Nemzet esetében jóval laposabb a cikk számok időbeni eloszlása

Ezt követően abba is betekinthetünk, hogy milyen kontextusban jelenik meg a Pegasus a 4 vizsgált médium híradásában. Ehhez egy picivel bonyolultab módszert használunk, amit úgy hívnak, hogy névelemfelismerés. Egy nagy méretű előre betanított nyelvi modell segítségével felimerhetjük a szövegeinkben jelenlévő névelemeket, névelem minden olyan főnév, amely valami specifikus, egyedi dolgot jelöl meg. Például a főváros szó nem névelem, de Varsó és Prága igen, ezenfelül névelemek a különböző intézmények, szervezetek nevei, a személynevek, email címek stb. stb. Ezekből a példákból már látszik, hogy miért hasznosak a névelemek a cikkek tartalmának átvizsgálásához, egy cikk névelemein keresztül láthatjuk vázlatosan a legfontosabb elemeit. Először tehát ketté választjuk a begyűjtött szövegeket egy kormány kritikus félre Telex és 24.hu és egy kormány közeli félre Magyar Nemzet és Origo, majd kigyűjtjük az összes névelemet és megszámoljuk melyik hány alkalommal fordul elő. Végül pedig a leggyakoribbakat egy szófelhőben ábrázolhatjuk, ahol minden kifejezés mérete a szó előfordulásának gyakoriságát ábrázolja. Az első ábrán látható a Telex, és a 24.hu cikkeiből készült szófelhő.

Az ábrán láthatóak egyrészt a Pegasus-hoz köthető szervezetek, pl.: a szoftvert kifejlesztő NSO cég, A nemzetközi oknyomozó munkában résztvevő Direkt36, Le Monde és Citizen Lab. Ezentúl láthatjuk az ügy magyar vonatkozásának szempontjából fontosabb politikusok neveit is, mint: Pintér Sándor, Kósa Lajos, Varga Judit, Szijjártó Péter, Gulyás Gergely, valamint több releváns magyar intézmény nevét pl.: Belügyminésztérium, Országgyűlés, Információs Hivatal. Végezetül észrevehetjük az ügy nemzetközi vonatkozásainak is a visszhangját. Megjelenik Izrael nem megleő módon. Szaud-Arábia, illetve Marokkó is előbbi több alkalommal is visszaélt a szoftverrel utóbbiról pedig kiderült, hogy magas rangú algériai katonai és politikai vezetők után kémkedtek a szoftver segítségével. Összességében tehát az így kapott szófelhő egy olyan hírfolyamot reflektál, ami elsősorban az ügy magyarországi vetületére fókuszál. A negyedik ábrán megtekinthetjük az Origo és a Magyar Nemzet cikkeiből azonos módszerrel készült szófelhőt.

Egy technikai részlet, hogy ezen az ábrán a szavak nagyobbak, ennek az oka, hogy kevesebb cikk alapján készültek, ami miatt az egyes névelemek előfordulási számának a szórása kisebb és ezért kevésbé differenciált a szavak mérete. Itt már kevésbé látszódik a nemzetközi hírekre való reakció, néhány releváns magyar politikus neve is megjelenik, mint pl.: Varga Judit, viszont a leggyakrabban olyan magyar politikusok neve fordul elő, akik ellenzékben voltak és nem voltak jelen releváns hatalmi pozíciókban a magyar állampolgárok Pegasussal való megfigyelése alatt Márki-Zay Péter, Gyurcsány Ferenc, Karácsony Gergely. Ugyan az előző szófelhőben is láthattuk az Európai Unióhoz kötődő kifejezéseket itt láthatóan jóval nagyobb a súlyuk. Ez alapján következtethetünk alra, hogy ennek a két orgánumnak a cikkjeiben nagyobb hangsúly került a botrányra vonatkozó reakció tárgyalására.

A blogposztban bemutatott mini elemzés több szempontból is leegyszerűsítő, viszont betekintést ad a 4 médium Pegasus-ra vonatkozó híradására. Az eredményeken látszódik, hogy a magyar fogyasztók attól függően, hogy milyen forrásból szerzik a híreiket eltérő konklúzióra juthatnak azzal kapcsolatban, hogy mekkora a jelentősége a Pegasus botránynak. Illetve a botrány magyarországi vetületének különböző aspektusaival ismerkedhettek meg. A Pegasus ügy természetesen ennek a jelenségnek az ábrázolására volt kiválasztva, tehát politikailag kevésbé szenzitív témá esetében nem feltétlenül számíthatunk hasonló mértékű eltérésekre.

Hivatkozások: